By Joel Thurtell

Born a slave, put Parisian chefs to shame, invested, and endowed a chapel for the white community on Grosse Ile. That is the story of Lisette Denison. Here is my sketch of her life, published with permission of the Detroit Free Press:

Headline: EX-SLAVE’S BEQUEST BUILT CHAPEL

Sub-Head: ST. JAMES EPISCOPAL CHURCH ON GROSSE ILE ROSE THANKS TO AN AFRICAN-AMERICAN LANDOWNER

Byline: JOEL THURTELL

Pub-Date: 2/25/2007

Memo: DOWNRIVER; BLACK HISTORY MONTH

Correction:

Text: It’s an amazing story — a black woman born into slavery seeking and finding freedom, traveling to Europe, wowing the Parisians by making flapjacks in the U.S. Embassy, then amassing enough wealth to endow a church that serves white people in metro Detroit.

Elizabeth Denison Forth was born a slave in the 18th Century. She was known to everyone as Lisette, the same nickname as her grandmother’s.

Lisette was the first black person to own property in Pontiac. A state historical marker in the city’s Oak Hill Cemetery notes that “in 1825 Elizabeth Denison, a woman of colour,’ purchased 48.5 acres of land from Pontiac’s founder, Stephen Mack, agent of the Pontiac Company. She became Pontiac’s first black property owner, but never lived on the property.”

She put enough money aside from her investments at the time of her death in 1866 to leave $1,500 towards the construction of an Episcopal church on Grosse Ile. The money was used in 1867-68 to build St. James Episcopal chapel.

The chapel, which is still used for early Sunday services year-round and for all services in the summer, was designed by English architect Gordon Lloyd, an island resident who also designed the Whitney mansion in Detroit, according to church historian Joyce Turin.

The chapel was the original church. A new sanctuary was built in the last century, and is attached to the old chapel.

The chapel has survived fire and a near miss by a World War II naval aviation trainee, whose airplane clipped off the bell tower in 1943. The tower has been replaced.

Before her death in 1993, Isabella Swan, a librarian, wrote a history of St. James Episcopal Church, a history of Grosse Ile and a little green-covered book about Elizabeth Denison Forth. In 1965, Swan published the 83-page “Lisette” herself.

Pat Lafayette is Swan’s niece, and she recalls how her aunt became fascinated with Lisette: “This woman went abroad, for goodness’ sake, and lived in Paris. She invested and had enough money to leave money for a church.”

Swan’s “Lisette” is a fascinating account of the life of a woman who could not read or write.

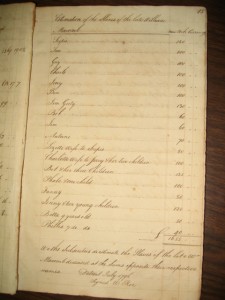

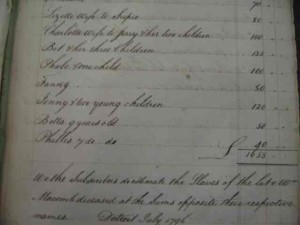

According to the book, Lisette’s grandparents may have been the couple listed only as “Scipio” and “Lisette” in an inventory of slaves owned by Detroit merchant William Macomb, co-owner of Grosse Ile, when he died in 1796.

Her mother and father, Hannah and Peter Denison, became free when their owner died, having ordered their eventual freedom. But in a famous and bizarre decision in 1807, Michigan Supreme Court Justice Augustus Woodward declared that three of the Denisons’ children – including Lisette, the oldest – must remain slaves for the rest of their lives, while a fourth could be free at age 25.

Though it appeared that Lisette was condemned to a lifetime of slavery, she managed to become free.

Swan’s sources are legal documents like Lisette’s several wills, and mostly, letters of Eliza Bradish Biddle, who hired Lisette as cook and housekeeper after she became free.

Lisette’s independence

I asked Lafayette, who lives on Grosse Ile, how Lisette became free.

Her aunt’s book doesn’t fully answer that question.

I talked to David Chardavoyne, a lawyer and legal historian in Farmington Hills. From Swan, Chardavoyne and a third historian, Mark McPherson of Grosse Ile, I think I now understand how Lisette pulled it off – with lots of help from white lawyers like Judge Woodward and Elijah Brush.

It’s an explanation replete with dates and facts.

But if you follow this explanation, you will learn important things about the history of our country as well as our state before it became a state. One of those things is the simple fact that despite being in the North, Michigan had slavery.

Why is that important?

“People tend to believe that the ugly legacy that is slavery is one that really only pertains to the South,” Martin Hershock, a history professor at University of Michigan-Dearborn, said this month.

“On the contrary, slavery was a national institution into the early 19th Century. Even after states like Michigan rid themselves of this evil, residents of the state continued to benefit from slavery.”

Chardavoyne notes that a British census of both shores of the Detroit River in 1782 counted 179 slaves among 2,191 people. Slaves were 8% of the population then.

There were three important dates for slaves, like Lisette, in the region:

1787: The Continental Congress enacts the Northwest Ordinance for administration of territories that are now the states of Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin and part of Minnesota. The ordinance bans slavery in those areas.

1793: The Canadian Parliament enacts a law gradually banning slavery. Lisette and two siblings are born before this law is passed.

1796: The Jay Treaty calls for the removal of British government from Detroit and the Northwest Territory that year, but allows Britons to hold onto their property, including slaves, in those areas.

Elijah Brush argued before Judge Woodward in 1807 that the Northwest Ordinance banned slavery, so Lisette and her siblings could therefore not be slaves. The lawyer for the Denisons’ owner – Mrs. Tucker – argued that the Jay Treaty allowed her to keep her property, of which the four Denison kids were a part.

Court makes its decision

Woodward ruled that before 1796, the Northwest Ordinance didn’t apply in Michigan because the British were in control of the region.

The Denison child born after 1793 could become free at age 25, following Canadian law, Woodward declared. But the other three kids, including Lisette, were born under British law and before the Canadian abolition law. So they must remain slaves the rest of their lives.

Bad news. So how did Lisette manage to become free?

In Chardavoyne’s opinion, Lisette and her siblings never were freed, legally. They went to Canada, where authorities were unwilling to pursue them because Woodward, in another case involving runaway slaves from Canada, ruled that the United States had no obligation to return those people to their owners. In tit for tat, the Canadians refused to return slaves like the Denisons to their American owners.

McPherson, in his 2001 book “Looking for Lisette,” says that Woodward ruled that slaves who went to Canada could not be brought back to the United States as slaves.

“Eventually,” said Chardavoyne, “the children returned to the United States and essentially nobody made a big deal of it and they lived the rest of their lives in Michigan.”

Lisette married Scipio Forth in 1827, but apparently Scipio Forth died before 1830, according to Swan. Lisette was hired by Eliza Biddle to cook and take care of her house.

Lisette traveled to Philadelphia and Europe with John and Eliza Biddle, taking care of their five children.

In Paris, Lisette earned a reputation for her delicious pancakes. She was invited to make flapjacks in the U.S. Embassy in Paris. She brought her own grill, embarrassing the ambassador’s chef with her fine cookery, according to Swan.

She was a great cook, a property owner and an investor.

And today, Lisette’s portrait hangs on the wall of a small room leading into the St. James chapel. In her will, she said she hoped the chapel would be a place “where the rich and poor should meet together.”

“This woman went abroad, for goodness’ sake, and lived in Paris. She invested and had enough money to leave money for a church.”

Pat Lafayette of Grosse Ile about Elizabeth (Lisette) Denison Forth

Contact JOEL THURTELL at joelthurtell(at)gmail.com

Caption: St. James Episcopal Church

Elizabeth Denison Forth, born a slave in the 18th Century, was called Lisette. She died in 1866, unable to read or write.

PATRICIA BECK / Detroit Free Press

In a scene reminiscent of a Currier & Ives print is the St. James Episcopal chapel on Grosse Ile. The chapel – originally the main church – was built in the 1860s with a bequest from Elizabeth Denison Forth, a former slave who invested in real estate and steamboat stock and was the first African American to own land in Pontiac.

The red door bears a sign reading “The Lisette Denison Doors.”

The Tiffany window was renovated and reinstalled in 1999.

A well-used doorknob on an inner entry door of St. James chapel.

Photos by PATRICIA BECK / Detroit Free Press

The stained-glass window was installed at the St. James Episcopal chapel in 1898 as a memorial to Susan Dayton Biddle, longtime organist and choir director. Susan was married to William Biddle, one of the sons of John and Eliza Biddle; Eliza employed Lisette as a housekeeper. In her will, Lisette asked William to use her money to build the church. He and his brother, Maj. James Biddle, donated land and funds to complete the building.

Illustration: PHOTO

Edition: METRO FINAL

Section: CFP; COMMUNITY FREE PRESS

Page: 1CV

Keywords: historical

Disclaimer: THIS ELECTRONIC VERSION MAY DIFFER SLIGHTLY FROM THE PRINTED ARTICLE